- U bent hier: Home

- Hammond

- Overzicht Uitvindingen Technische uitleg 3D-film (Engels)

Uitleg 3D-Film

Hier volgt de uitleg over de werking van het 3D-systeem, het stereoscopic motion picture systeem, welke Laurens Hammond op 25-jarige leeftijd in 1920 uitvond. De film werd met grote snelheid wisselend op het linker en het rechteroog geprojecteerd.

Het was toen zijn tijd veel te veel vooruit en werd pas in 2010 een standaard in de film-wereld nota bene 90 jaar later.

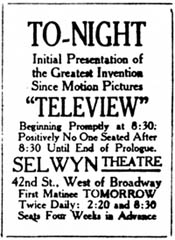

New York Sunday 31 dec. 1922 over de televieuw:

The patent for the basic system was filed by Laurens Hammond (1895-1973) on March 2, 1921, so one can assume the actual development (tests) preceded this date. So far, I have found three patents, though there should be four.

His first demonstration was with slide projectors (still images) which impressed enough to obtain apparently several hundreds of thousands of dollars.

They needed to locate a theater that they could literally take over for (hopefully) an extended period of time.

That theater was the 964 seat Selwyn, 229 West 42nd Street, NYC.

Opened only four years earlier, the Selwyn was a legitimate house up to that time, showing films only on occasion. It didn't become a movie house until 1934.

The first written record of this momentous technology appears to be in the New York Times (NYT), 22 Oct 1922.

Accounts at the time also mentioned a William F. Cassidy as an ill-defined associate, though Hammond's not mentioning him kind of diminishes his importance.

By that time Hammond and associates had shot a feature film, M.A.R.S. Hammond said he wrote the screenplay, though IMDB lists Lewis Allen Browne. It was made by, at or with 'Tilford Cinema Studios.' And by the time the show opened, they also had produced what I estimate was a one reel prologue.

M.A.R.S. is the world's second 3D feature film.

At some point Hammond stumbled onto the stereoscopic shadowgraph concept. I have not found any documentation about how this came about.

Teleview was not an original idea, which Hammond even admits in his patents, but he made it work where previous attempts didn't (such as Jenkins, 1897)

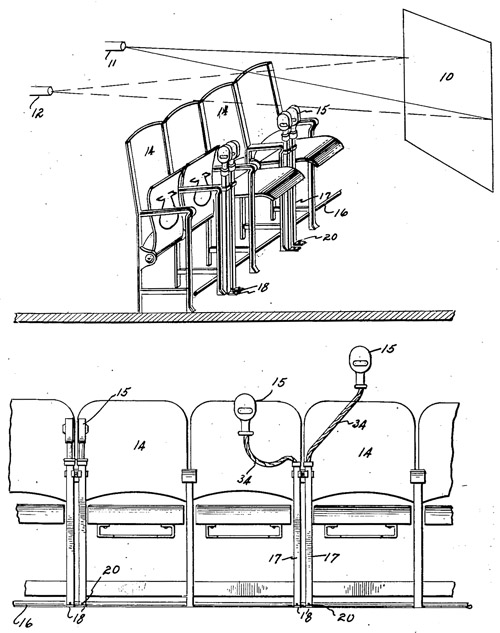

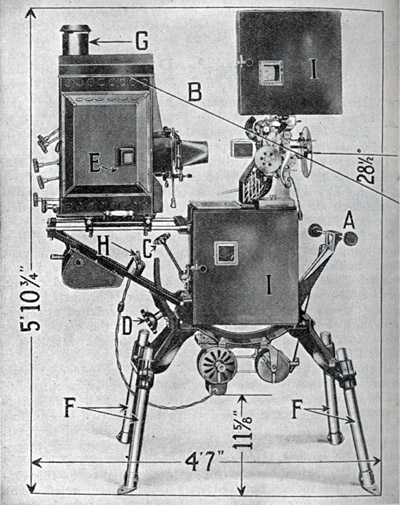

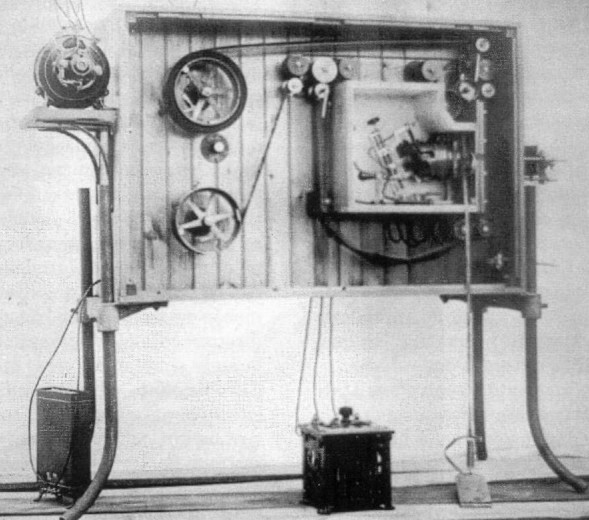

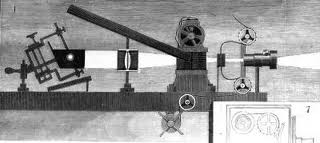

In the theater, two normal projectors were linked with sync motors, so they ran in absolute sync. They were Power's projectors, the current model of the time being the six-B. Very simple machine for modification.

This allowed him to precisely control the AC frequency, which in the U.S. is 60 cycles (hertz or Hz) This was a key aspect of his idea. (pas later zou dit hem op het idee van toepassing voor zijn klokken brengen...)

The projectors were driven by this regulated AC, via their own sync motors. If the AC frequency was raised, the projectors would run faster. Very accurate control.

The left film was in the left projector and right film in the right.

The projectors were in frame sync, but the shutters were out of phase sync (look carefully at the patent diagram)

Attached to each and every seat in the theater were the viewing devices. They were stored neatly in front of the seat arm. One sat down and grasped the viewer and pulled up. It was mounted on a flexible neck, similar to some adjustable "goose-neck" desk lamps. You twisted it around and centered it in front of your face, kind of like a mask floating just in front of your face.

In spite of the imagination of the various artists, the viewing device would have been no farther than maybe 4" from one's face in order for both eyes to see the entire screen.

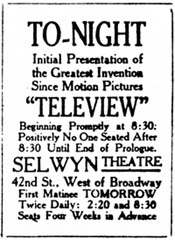

In the round enclosure was a very small (1 /34" diameter), 12 volt AC, 3-pole sync motor. I believe this motor went on to become part of his Hammond organ a few years later.

Attached to the motor was a miniature version of the projector shutter. (Later zou hij een variatie op dit systeem in een spionagecamera gebruiken, welke men later onder een vliegtuig hing...)

The viewer had a window permitting both of your eyes to see through the shutter to the screen. There was glass in the windows to prevent you from chopping your nose off and insulate the sound of the device.

The AC system powered this device and the sync motors automatically would go into "phase" so all the viewers in the theater would be exactly the same.

This was pretty good stuff for 1922.

But Hammond had to work out the flicker problem.

Normal film speed at the time was 16 frames per second.

Yes, we know this varied a lot, especially to faster speed such as 20 fps.

But 16 is what he shot his film at and specifies in his patents.

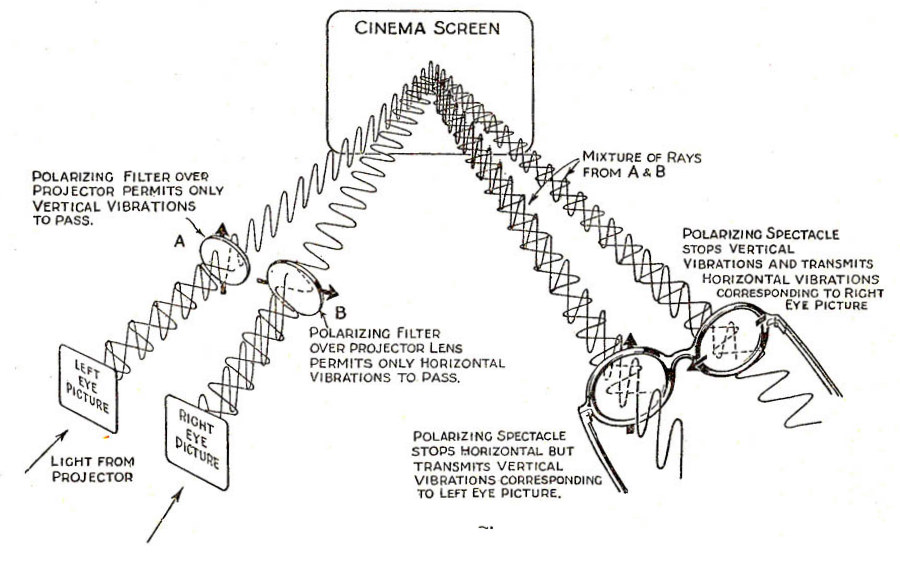

A shutter-based system such as this is sequential. That is, our eyes get the left and right images one eye at a time, first the left, then the right. This is a frame sequential method. We'll get into problems with this method later.

At 16 fps, the L-R sequence would cause highly irritating flicker.

But Hammond chopped up each frame into three flashes, versus one or even two.

The sequence was: 1L-1R-1L-1R-1L-1R- 2L-2R-2L-2R-2L-2R and so on.

Three alternate flashes per eye on the screen. This increased the flicker frequency to invisibility.

As you would look through the device, your left eye would see only the left image, with your right eye being blocked. Then the shutter in the device blocks the left eye, unveiling the right eye. All in sync with the left and right images being flashed on the screen.

Even through today's eyes, this system would look good. Top notch except for the time delay between the left and right views. The average person wouldn't notice, but it would be bothersome for fast subject motion. All sequential methods have this drawback.

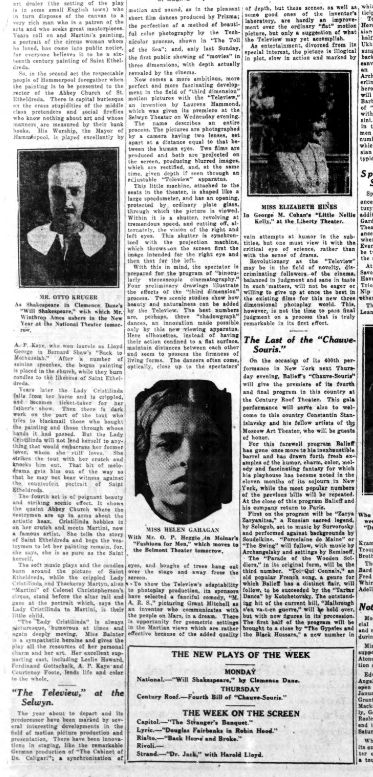

The grand premiere was on 27th of December 1922.

What is amazing historically is that the first 3D film exhibited to a paying, theatrical audience was premiered just four days earlier:

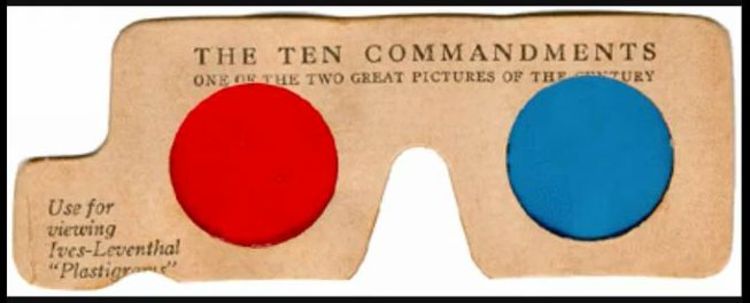

William van Doren KELLEY'S PLASTICON MOVIES - MOVIES OF THE FUTURE, a one reel, anaglyph short, shown at the Rivoli Theatre not even 8 blocks away from the Selwyn.

Anybody got a time machine?

According to the reviews, the show started with a prologue composed of still 3D artwork and photos, along with motion footage of the Canadian Rockies and scenes of Navajo and Hopi Indians!

I believe this footage was probably not more than one "reel" and likely produced before the feature to work bugs out of the camera.

There is no significant information about the camera used, sadly.

While the projectors were being threaded up with the feature, one of the highlights was the 3D shadowgraph. Hammond filed for a patent on this concept on 23rd of January 1923.

It was a simple idea. Move the normal projection screen out of the way (the projectors were not used for this act) and replace it with a translucent type. Imagine a simple sheet. It is possible they had a screen fabric that could be used both ways.

At the back wall of the stage (about 30' deep) were two, high-intensity arc lamps facing the screen. They were spaced side-by-side perhaps 3" or so apart and had shutters exactly like on the projectors and the viewing units, to alternately block one light, then the other.

When a performer stood between the lights and the screen, the audience saw a silhouette. And because of the two lights and shutters, when viewed through the Teleview viewer, the silhouette was stereoscopic and would appear to float off the screen into the auditorium.

As this was a live act, the audience was even more amazed than with the films. This was an extremely successful part of the program and I'll cover 3D shadowgraphs in more detail in a separate chapter.

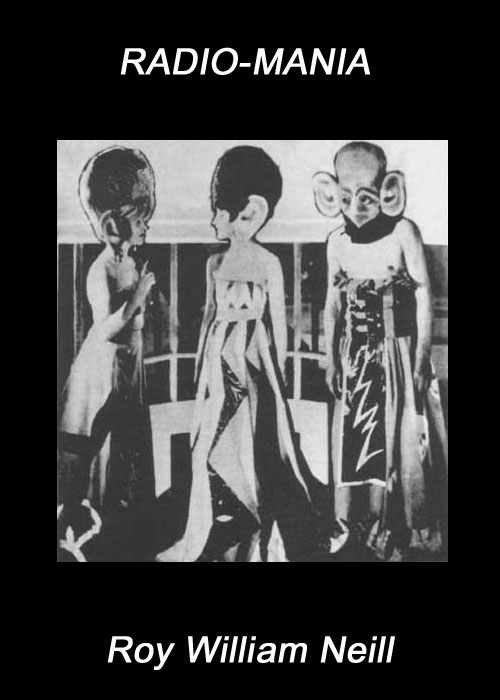

Lastly, the "fantasy-comedy" feature M.A.R.S. was presented. From what I have gathered, this was the least-liked aspect of Teleview.

The press was quite impressed by the Teleview concept, but after only 24 days, on 20th of January 1923, the show closed. It was announced in the New York Times that a new show would be seen in March, at the same theater. Teleview was never heard from again.

In light of Hammond's crying in his pillow all night long, this shouldn't surprise. Technically it was a wonder. Commercially?

The 3D shadowgraph concept was seen around the world in a few places over a number of years, though not to Hammond's benefit.

M.A.R.S. was ultimately retitled RADIO MANIA (or RADIO-MANIA) and seen 2-D nationally in '23-'24. Interestingly, the distributor was W. W. Hodkinson, the founder of Paramount Pictures distribution company which Zukor & Lasky eventually took over forming Paramount Pictures Corp.

Zie ook: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Man_from_M.A.R.S._%281922_film%29

en http://www.brightlightsfilm.com/68/683D.php

Omdat het destijds veel te duur was om elke bioscoop ervan te kunnen voorzien, vond Hammond het groen-rode brilletjes-systeem uit dat vandaag de dag nog steeds gebruikt wordt.

Hier nog een andere versie, van de 3D-Story:

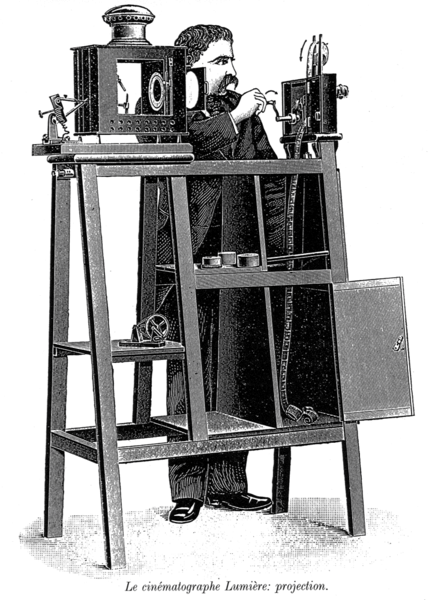

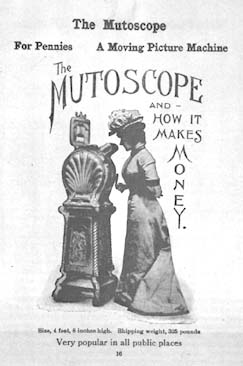

The "novelty" that concerned Griffith and disturbed much of the movie-going public was in line with the movement away from what Tom Gunning calls the "Cinema of Attractions" and toward cinema's narrative form as established by Griffith. Gunning notes, "]n the earliest years of exhibition the cinema itself was an attraction. Early audiences went to exhibitions to see machines demonstrated . . .

It was the Cinematographe:,

the Biograph,:

or the

or the Mutascope:

that were advertised on the variety bills." The Teleview could just as easily be added to this list. Before the release of the film, the Teleview was advertised in the Times as "The Greatest Invention Since Motion Pictures." It was also announced thus: "First the Telescope, Then the Telegraph, Then the Telephone, and now Teleview,"without naming M.A.R.S. as the film to be shown. Even during its stint at the Selwyn, advertisements did not name the movie being played. Rather, the Teleview was characterized as the attraction, showcasing an "Entirely New Form of Entertainment" that "Recreates Natural Sight, Just as the Telephone Recreates the Human Voice." Film Daily called the opening night of M.A.R.S. the "world premiere" of the "Teleview." The public would not even be given the title of the film until a mere ten days before its premiere.

The movie premiered at the Selwyn Theater on Dec. 27, 1922. The next day, the Times reported that M.A.R.S. — a film that "unfortunately did not prove very impressive as a dramatic composition," being "drawn out to a tedious length and burdened with much dreary humor" — will be showing at the Selwyn for an "indefinite time." The article noted that the film's "first impression was mixed," but M.A.R.S. "illustrated the use of the third dimension" that "permitted a number of bizarre effects" in the Martian sequences. However, the film's reportedly effective use of the third dimension was not a sentiment shared by all. The editor of Film Daily, known only as Danny, found the novelty interesting — even comparing its "futuristic effects" to those of Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. But the two films are far from cinematic equals. Danny found the experience of viewing a film through the Teleview to be quite painful: "Trifling eye strain results, and one is inclined to become a bit stiff through remaining in one position." As far as the movie itself, he said it was "too long and should be cut."

On January 20th, less than a month after premiering for an "indefinite time" at the Selwyn, the Teleview was pulled from Broadway. On its final day, the theater held an event called "Thirty Years of Motion Pictures," which began with a showing of The Great Train Robbery and ended "with an exhibition of the Teleview pictures." This event, though marking the end of its run on Broadway, continues to compare M.A.R.S.with movie classics that history has remembered, even after the hype had faded. But, as advertised, M.A.R.S. was essentially reduced to a Teleview picture.

The "futuristic" technology of the Teleview was followed at the Selwyn by a form of entertainment that required little, if any, technological innovation: a play, The Dagmar. The audience would also follow this sentiment as The Dagmar would go on to enjoy a longer stint on Broadway than the Teleview.

But was it the technology or the film that moviegoers were rejecting? Fortunately, there is a way to separate the film from its technology. Six months later, M.A.R.S. would be rereleased in normal 2D, a strategy that the makers of the Teleview had noted as a possibility if the system proved unsuccessful. The film was also renamed Radio-Mania, a title that reflected the surge in radio broadcasting that swept across the country in the early 1920s.

Susan Douglas, in her book Listening In, claims that, by 1922, "radio phoning [had] become the most popular amusement in America." Radio, like 3D films, was a novelty in that decade. Many people would tinker with their ham radios as a hobby. Furthermore, some would even try to use radio to contact "The Ethereal World," — or as Douglas notes, "otherworldly contact;" magazines even sponsored "How Far Have You Heard" contests. The plot of M.A.R.S., or Radio-Mania,

incorporates these fads: it is about a "Radio nut" who makes contact with "otherworldly" Martians via radio waves — only to wake up and find it was all a dream. Advertisements of the film, aimed at exhibitors, stated, "Every day thousands of dollars of publicity space is being given in this country on Radio, the most widely advertised subject of today," thus giving the movie "selling possibilities that place it at once in the class of sure money-makers."

Just as it had exploited the 3D effect to enhance its Martian terrain, so was M.A.R.S. resold to the public as a timely exploitation of the radio craze. Though the film's release was briefly noted in the Times, it did not generate the buzz that its 3D counterpart created. The film would never again appear on Broadway and would be relegated to obscurity — just like the Teleview.