Laurens Hammond

- Laurens Hammond Story

- Het Patent

- Het privéleven van Laurens Hammond

- Overzicht Uitvindingen

- Hammond 25 years (Eng)

- Hammond 50 years (Eng)

- Fabrieken, relaties en privé-bezittingen (Eng)

- Hammond, de uitvinder

- De Reddende Wrigley Deal

- Kort overzicht Hammond factory (Eng)

- Hammond versus pijporgel 2004

- De Hammond Archieven 1

- De Hammond Archieven 2

- De Hammond rechtzaak (Eng)

The following article by John Majeski Jr. appeared in the May 1960

issue of "Music Trades" magazine and provides a unique insight

in the first 25 years of Hammond history...

All information in this article is only accurate as far as known at that time... in 1960!

Henry Ford's marketing foresight may have been slightly clouded when he uttered some of his opinions, notably "The public can have any color Model T they want, provided it's black."

But twenty five years ago last month when he placed the first order for a Hammond Organ, a week before it was announced to the public, he displayed a prophetic recognition of the organ's future market.

"In twenty years, there should be one in every home in America," he declared to Emory Penny. Penny, then sales manager of Hammond Clock Co. and the man who personally took the order after a demonstration in Ford's Dearborn factory, was also told, "you should sell organs at $300.

And don't fall into the hands of those Eastern Bankers." That night enroute to the First and only Industrial Arts Exposition which opened at Radio City in New York, Penny wrote Laurens Hammond, "I feel he would lend us half a million dollars."

During the intervening quarter century, Hammond's pioneer organ trail has developed into a superhighway with no speed limits posted. Almost one billion dollars worth of electric (and electronic) organs have been sold since Pietro Yon, famed organist of St. Patrick's Cathedral, demonstrated the Hammond on April 15, 1935 at a press party. Hammond made news on that day.

Fritz Reiner and Deems Taylor also played the organ as accompaniment for Lily Pons, Rosa Ponselle, Giovanni Martinelli and Colette D'Arville. News reel men and reporters loved it and awardedit an avalanche of publicity.

Unrecognized by most industry seers and merchants, a new era in music retailing had been launched. In a year still blighted by unemployment, the first fifty Hammond dealers sold with ease at $1,250 each all 1.400 Model A organs shipped. Last year (1959) over four hundred Hammond dealers sold over sixty million dollars worth of organs at retail out of an estimated total of approximately one hundred and ten million dollars worth of organs sold.

"The smart thing for an inventor to do," once observed Laurens Hammond, "is to put together the old tricks that you have done before." An historian might add, "and also what others have done before." Without detracting from Hammond's achievement of inventing and marketing the first commercially feasible non-pipe organ, what old tricks sired Hammond's magical box?

Unconsciously, the key elements of the organ were created in 1920 when Hammond patented a "tickless" spring driven clock and also marketed a three dimensional movie viewer powered by a synchronous motor. Neither succeeded commercially, but in 1928 they were fused into the original Hammond Clock, "tickless" and synchronous motor driven.

Clock companies burgeoned and as late as 1931, just before the deluge, Hammond Clock earned $577,348. In 1932, over 150 electric clock makers ceased manufacture or liquidated. For the next four years, Hammond Clock lost over four hundred thousand dollars. The electric clock market had decayed to .89c premiums given away as Wrigley chewing gum premiums. Staff was drastically cut. The force of six office boys was cut to two. One of these was Stanley M. Sorensen, Hammond president since 1955.

In 1934 Hammond's annual report which showed a loss of $137.176,- The undreamed promise of a golden era was modestly announced: "We have continued our development work on new items and plan the introduction of a new product during the coming year. This item when introduced will substantially augment our sales volume and further improve our operating results."

Unrecorded save in the patent office and on yellowed newspaper clippings, since 1890, there had been a steady stream of inventions and technical papers on pipeless organs. The achievement of Hammond in synthesizing a rotating tone generator, synchronous electric motor, keyboard and amplified speaker is outstanding largely in view of the efforts of scores of contemporaries who were seeking the same end and had common access to the same generic elements. None had succeeded with a serviceable instrument, adaptable to existing organ literature.

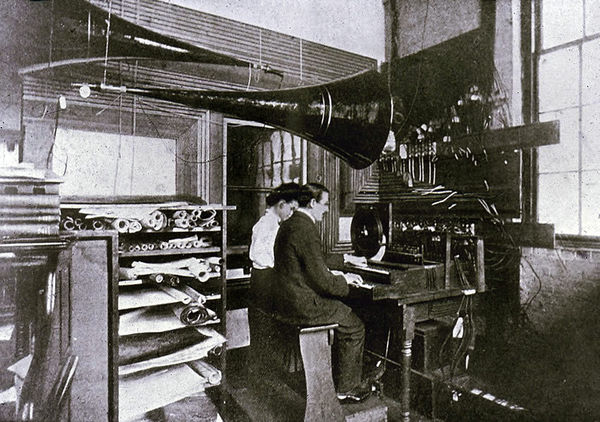

At the turn of the century, Thaddeus Cahill had filed five voluminous patents comprising 322 pages for his Telharmonium. Cahill's Telharmonium employed rotating magneto-electric tone generators, each one man sized.

In 1908, he demonstrated his unit, the size of a small powerhouse (see pictures) in New York City and elicited the praise and support of Mark Twain. For a time, his organ music was piped over telephone lines to subscribers like Muzak. Unfortunately, his only source of amplification was the telephone mechanical diaphragm, a poor source of transmission. When his Telharmonium interfered with telephone communications, Bell Telephone discontinued the service. J. P. Morgan reputedly was the source of complaint when during an important financial transaction on the telephone, the conversation was drowned out by a flood of organ music.

Photo-electric tone production had been explored with prototypes dating back to 1916 by a number of inventors including Van Der Bili, Hugonoit, Potter, Toulon, Spielmann, Goldthwaite, Hardy, Lesti and Eremeeff. Pure electronic musical tone generation began with Duddell in 1899 and included Miller, Bethenod, DeForest, Mager, Coupleaux and Givelet, Vierling and Kock, Langer, Helberger and Lertes, and Theremin, whose instrument enjoys a tenuous survival.

Telefunken in Germany marketed the Trautonium:

As early as 1931 Richard H.Ranger's pipeless organ was heard in broadcasts over Radio Station WOR, Newark, N.J.

Hoschke had already developed the windblown harmonium reed electronic organ, marketed as the orgatron.

George of Thomas Organ

In Cincinnati, OH. Thomas George a young telephone engineer who liked to play the organ, started building one in 1932 as a hobby. In 1934, he filed some patents which came to the attention of Hammond, then mid-way between patents and prototype. John Hanert, Hammond's chief engineer, visited him in Cincinnati and persuaded him to join his firm. George remained with Hammond until 1941. In 1955 after unsuccessful attempts with scores of electronic companies, several of which are now (in 1960) again contemplating organ manufacture, he succeeded in having Pacific-Mercury use his patents. His organ is now marketed under his surname as the Thomas Organ.

The principal element in the electric clock manufactured by Hammond Clock Co. was the small, rugged, synchronous electric motor. Hammond had first used the motor in his Teleview, a three-dimension motion picture which closed one month after opening to critical acclaim at the Selwyn Theatre in New York City on Dec. 27, 1922. The motor powered a special viewfinder in which a revolving shutter enabled the spectator to view in three-dimensional form, the screen upon which two projectors simultaneously cast an image.

At that point the only relation of music to the synchronous motor lay in the orchestral accompaniment composed and conducted by Paul Tietjens, noted American composer and one time brother-in-law of Hammond. John Borden, Chicago mining heir, whose daughter later married Adlai Stevenson, cheerfully lost $120,000 in the venture. Hammond acquired a permanent interest in the synchronous motor.

A $350 weekly royalty from Ziegfeld for a simplified version of the viewer used for trick effects in the 1925 Ziegfeld Follies, encouraged Hammond to work as an independent inventor instead of joining Western Electric at $64 per week.

The following year he joined E. F. Andrews, as a partner in the Andrews-Hammond Laboratories. Andrews - a former radio manufacturer - and Hammond invented the A-Box :

a temperamental mechanism with a penchant for exploding that in quiet moments enabled a wet cell radio to be played by being plugged directly into an outlet. Within less than a year, radios without batteries were on the market and the A-box part boon, part menace was dead.

From his partnership with Andrews - who for many years served as a director of the Hammond Co. - being one of the principal original stockholders, the tiny company had the rudiments of an engineering research staff.

During its brief A-Box period, it also acquired a sales staff: F. H. Redmond, vice-president and general manager until his death in 1953. And Emorv Penny, sales manager until he resigned in 1944 to head Penny-Owsley Music Co. in Los Angeles.

The clock market dies and Penny met Hammond at the 1926 radio show while he was advertising manager for a radio company. Hammond met him casually, they liked one another and he accepted his offer to sell A-Boxes. Penny (see picture) proved to be an indefatigable salesman who sold A-Boxes, electric clocks by the thousand, $25.00 Hammond electric bridge tables in the depths of the depression in 1932 and finally the first Hammond Organ to Henry Ford.

In 1928, the future organ giant was incorporated as the Hammond Clock Co. Hammond had found a new use for synchronous motor applied to his old 1920 patent for a "tickless" clock. Earnings were substantial and reached $507,120 after Federal Income taxes of $69,627 in 1931. (In 1959 Hammond paid $4,511,009 federal taxes on income of $8,786,796).

The following year, in addition to general economic woe, 150 clock makers ceased operations and glutted the market with distressed, below cost, clock merchandise. A blood red statement of loss on Hammond's earnings report exercised a coercive inspiration to find new uses for the company's electric motor.

Depression and bridge tables

In the Fall of 1931 the company marketed its Hammond Electric Bridge Table, retailing at $25.- Powered by an electric motor, the table in its brief life of one year (none was ever built after 1932) earned revenues of $300,000 and verv possibly saved the company.

Another abortive attempt at utilizing the motor was in the development of a motor driven record turntable, the first ever proposed in a field hitherto powered by spring driven units of unstable speeds.

The innovation failed due to chaotic conditions in the economy and in the radio industry in particular.

By 1933, Hammond's little synchronous electric motor had powered three-D movie viewers, clocks and clock calendars, as well as bridge tables. Currently and without profit, they were helping to produce music from other firm's records. Thirty years earlier, Cahill in his Telharmonium had empirically demonstrated Helmholtz's theory of tone: that tonal timbre depends on the order number and intensity of one of the partial structure of a musical tone.

In simpler terms, the wave length of any musical tone may be described mathematically. With the advent of electricity, scores of inventors had demonstrated that musical sounds could be reproduced by controlled electrical wave lengths instead of mechanical force. (Organ pipe air column, vibrating string either struck, plucked or bowed, etc.)

Eremeeff's pipeless organ had already been well received in a concert given under American Guild of Organists auspices. B.F. Miessner's encyclopedia patents cast a shadow on many developments not already patented. R.C.A. in 1930 had paid Theremin $100,000 for his "easy to play" instrument, envisioning a vast home market. A pre-sputnick beep! Early in 1933 a peculiar "beep" emanated along with the sound of records being played on the experimental phonograph turntables in the laboratory of the Hammond Clock Co. At the end of the day, Hammond asked the firm's assistant treasurer W. L.Lahey, whose office was nearby, if he had heard anything unusual. Lahey, who also was organist at St. Christopher's Episcopal Church in Oak Park, Ill., replied that he had heard a flute. "You did?" replied Hammond. "Well. I've made an electric flute."

The next day Hammond and his engineers began to explore in earnest the infinite possibilities of producing conventional musical tones by electric synthesis. A non-musician, Hammond relied upon Lahey to appraise the qualities of the tones he produced. Although unconfirmable, it is inconceivable, that Hammond and his staff were not intimately cognizant of all previous experiments in the field.

Hammond bought a second hand piano for $15 and threw away everything except the keyboard. Judging from anecdotes that have filtered down from associates, Hammond's laboratory experimented upon a wide variety of tonal production methods.

Unlike most of his predecessors in the field, Hammond's concept of an invention was happily colored by his experience as a manufacturer. Every product is a theory modified by the exigencies of manufacturing and marketing. Hammond by his work demonstrated implicitly the ascendancy of rugged serviceability and ease of manufacture.

By mid 1933, Hammond was concentrating on his own original tone generator, an invention prefigured by Cahill's Telharmonium three decades earlier. Instead of being of powerhouse dynamo proportions like Cahill's, Hammond's original adaptation of the principle were tiny steel wheels, the size of a half dollar. For rugged serviceability and ease of manufacture, Hammond's tone wheel surpassed in practicality all previous exploration.

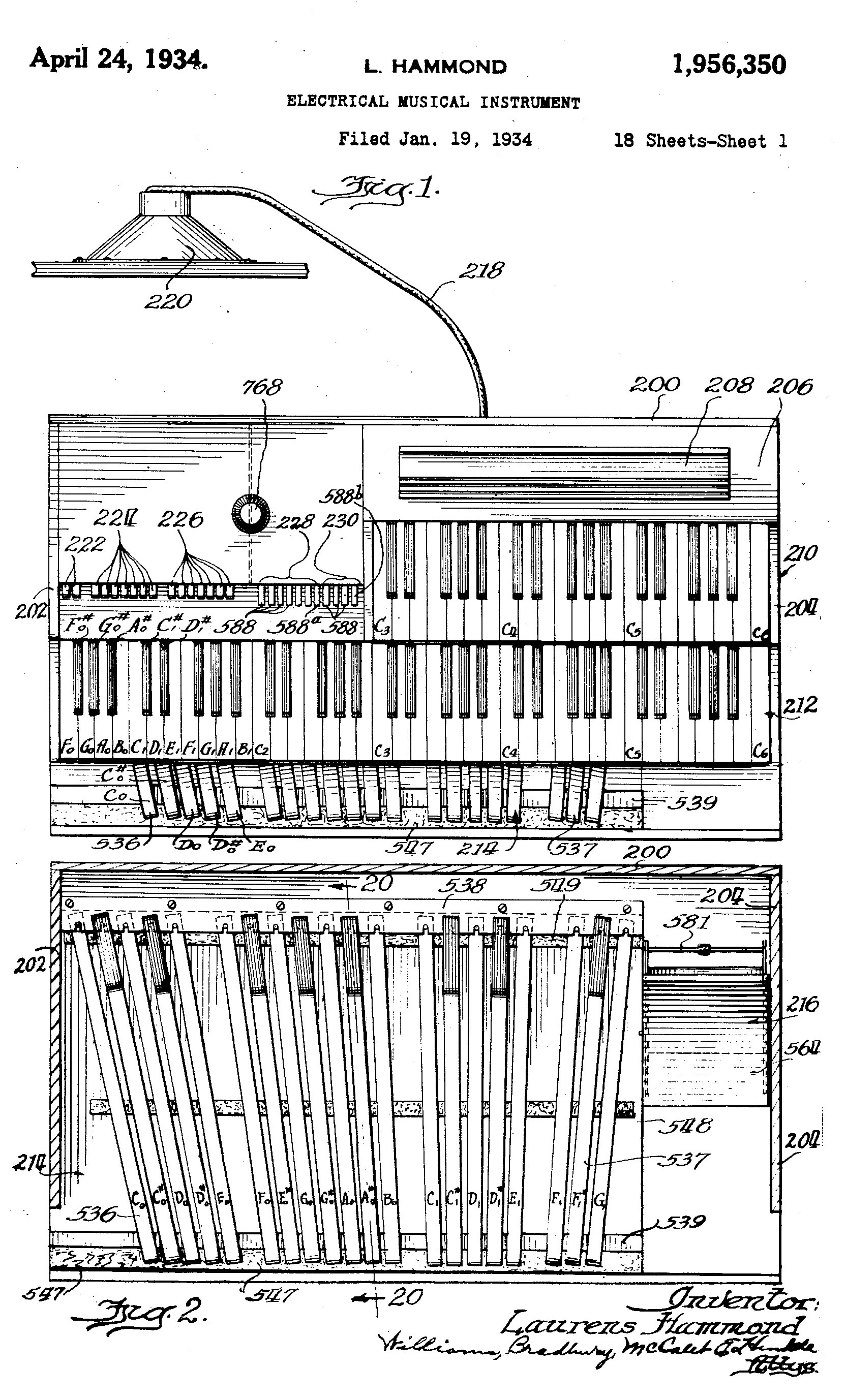

The slight departure from some of partials found in the tempered scale and listed in Hammond's patent No. 1,956,350 are perceptible only under laboratory analysis.

On Jan. 19, 1934, Hammond and his organist, Louise Benke, also typist, filed an application for a patent after demonstrating the new instrument in the basement of the Patent Office. With unprecedented speed, the patent was granted on April 24, in the hope that it would create employment in an economy heavily dependent upon WPA. Throughout the balance of the year, and according to some reports, virtually until a few days before its public debut, the organ underwent constant refinements.

Ironically for a company that has pioneered the theory of exposure, more exposure and still more exposure, the first Hammond organ was bought by Henry Ford instead of being sold to him. Ford actually beat a path to Hammond's door before "the better mouse trap" was available.

Mr. Ford orders organ

Early in the blustery, snowy morning of Feb. 7, 1934, two Ford Motor Co. engineers walked unannounced into the Hammond Clock Co. plant on Western Avenue in Chicago. Embarrassedly they explained to Redmond and Penny that a few days earlier, Mr. Ford had told them, gesturing with his hands, to build an electronic organ, "so big, by so big, by so big."

Two months later Penny in demonstrating the organ to Ford, understood their embarrassment when he heard the industrialist declare, "I never let people know what I am buying or they will charge me too much."

The Ford engineers intimated cautiously that Mr. Ford's requests were instinctively executed immediately in an "or else" atmosphere. Equally moved by the great man's appeal and their self-preservation reflex, they had explored the U.S. Patent office and to their intense delight had found Hammond's patent. It fitted perfectly Ford's specifications of "so big, by so big, by so big." Could they please buy one immediately?

Hammond explained that the production prototype would be displayed in New York City at the first (and only) Industrial Arts Exposition on April 15, and would be available after that date. A few days later, Ford extended a personal invitation to Hammond to "bring the organ to Dearborn when ready."

Early in April, 1935, the first Hammond Organ Model A left the plant en route to Mr. Ford and its New York debut. For economy reasons, it traveled in a well worn, battered Ford panel truck, chauffeured by Penny, the sales manager and John Hanert, chief engineer. Penny recalls that he did all of the driving en route because of Hanert's tendency to doze at the wheel.

Ford's appointment was for 7:30 a.m. and to ensure promptness, Penny and Hanert drove up to the main gate of the Dearborn plant at 7 a.m. "What an hour for demonstrating an organ," recalls Penny who now retails from five plush stores with twelve station wagons for outside selling.

Penny recalls that after bumping over interminable rutted, muddy roads, an unforeseen field test of the organ's durability, they were waved up to a building, "with the most beautiful wooden floor I have ever seen." Penny hesitated to drive in with his gritty, muddied tires but was hospitably welcomed in. "I certainly hated to drive a truck over that gorgeous floor."

Some musicians with antique, hillbilly instruments arrived - and finally at 8 a.m. Ford entered imperiously. At first Ford didn't even look at the organ. Greatly interested at that time in "Barn Dancing," Ford said, "Listen to the musicians, we are going to play for the kids." Penny listened attentively and recalls in his diary that like many great men, "Ford had little interest or enthusiasm except for his own products."

Ford on soybeans and cigarettes

Finally Ford listened to Hanert demonstrate the new organ and expressed his terse and accurate appraisal of its future: "In twenty years, there should be one in every home in America." At 11 a.m. with quiet affection, he announced, "Mother is waiting for me for lunch, these gentlemen will take care of you." Penny thought, "four hours of listening and still no sale."

Penny and Hanert were ushered into a sumptuous executive dining room whose appointments belied the food. The weird assortment on the luncheon plate defied both palate and analysis. "Soybeans," clarified one of his tablemates furtively, "Mr. Ford says they're good for you and you have to like them too." Penny reluctantly downed his first and last encounter with Ford's ubiquitous soybean and before horrified eyes restrained him, had almost succeeded in lighting a cigarette. "Mr. Ford does not permit smoking," chorused his hosts apprehensively.

Ford's advice on buying

After luncheon, Ford returned and showed Penny and Hanert through his Greenfield Dearborn museum. "See that big beautiful locomotive," the mogul gestured, "I bought it for scrap." "I never let people know what I am buying or they will ask too much." Ford than asked the price of the organ, learned that it was $1,250, ordered a subordinate to buy one and said good-bye.

Ford's homey adage, "History is bunk." ironically summarizes his historic first purchase of a Hammond organ. Publicity myth makers in official literature attribute the first sale to George Gershwin, pallid copy compared to the truth of Ford. Several dealers in widely separated areas also erroneously claim the distinction of the first sale.

Hammond's early organ is still on exhibit at the Greenfield Museum in Dearborn along, with "firsts" by Ford and Edison. After a quarter of a century, it plays on with a record of minimal service. Hammond later accepted a personal invitation to visit Mr. Ford. Ford offered to lend him money and engineers. Hammond politely demurred. And judging from Hammond's historic growth and earning pattern, Hammond obviously declined Ford's advice "to keep the price down and not make more than $20. profit on each organ."

A fifty per cent chance exists that Ford's correspondence with Hammond was picked up at the post office, sorted and placed upon his desk by Stanley M. Sorensen, an energetic twenty-year-old mail clerk of tenacious Norwegian origin. Sorensen had joined the clock company as a mail boy on August 25, 1931 after graduating from High School that Spring, aged 16. Elected president in 1955, it was his first job and came only after two months of haunting employment agencies. While some of the older boys received only $6 per week, for some unknown reason, Sorensen started at $8. Two years later, thanks to the NRA (National Recovery Act) he received his first big raise.

The Roosevelt administration had declared certain minimum wage standards. To meet the requirements, the companies fired four of their six boys and apportioned the work and pay to the pair that included the company's future president. Dealing 2,000 hands of bridge Sorensen's first assignment requiring personal responsibility occurred a few weeks after he joined the firm. Hammond ordered him to deal out one thousand hands of bridge manually, and also on his newly invented automatic bridge table. Each hand had to be tabulated in order to be certain that the mechanical bridge table shuffled and dealt the hands with no slips. After many long days of compiling and shuffling, he personally presented his tabulation to Hammond, elicited the word, "Great" and went back to shuffling mail bags.

By 1940, Sorensen after night courses in accounting at Northwestern University, had risen to the accounting department and was earning $30 per week. Like all employees when he married that year, he felt entitled to a raise. Company officials, perceiving no appreciation in his value to the firm because of a change in his marital status, declined his suggestion, although the following year he was increased to $33. The day Sorensen quit!

In 1941 with the economy rising under stimulus of defense contracts, Sorensen feeling that he "wasn't moving fast enough," negotiated a new job with a small firm, that considered him a bargain at $60 per week. When he walked into general manager Redmond's office to ask how soon the Hammond Co. could release him, "everyone got excited and said you can't do that."

Since Sorensen became president in 1955, Hammond has shown its greatest fiscal progress. A steely, soft-spoken individual, he wryly remembers learning years later that one of the directors in 1941 had recalled his proposed resignation at that time with the statement, "we should have fired that blockhead then."

During the War, Sorensen forged ahead rapidly on the strength of his performance in renegotiating government contracts.

In 1946, while Redmond and Merrill, the two chief administrative executives fell ill, Hammond returned to active administrative duties and began to rely on Sorensen for administrative assistance. Later Redmond came back to work half days and Sorensen assisted him. While chauffeuring him back and forth to work, he became acquainted with top management policies.

When Redmond died in 1953, Sorensen succeeded him as vice-president and general manager.

In the candid opinion of one of the promoters of the one and only Industrial Arts Exposition which opened in New York City on April 15, 1935, "the show was a real flop but Hammond never had it so good." The promotion of a product without parallel or precedent is a challenge that fortunately rarely faces a publicity agent (in recent years more mellifluously termed a public relations counselor) Erwin Wasey, Hammond Clock's advertising agency, fortunately dumped the problem into the cunning bands of Constance Hope whose clients included Fritz Reiner, Martinelli, Lily Pons, Jascha Heifetz and Rosa Ponselle.

Hope solved the problem of blending the image of a serious musical instrument with one of popular music appeal by staging a press party with a surfeit of famous musicians. All were front page copy for family newspapers of the period and the pictures gleaned from the party could pass for contemporary advertising messages captioned, "Have Fun at the Organ."

Pietro Yon, organist at St. Patrick's Cathedral and Fritz Reiner, now Chicago Symphony conductor, demonstrated the organ and later Martinelli, Melchior, Lily Pons and Rosa Ponselle broke into contrived, spontaneous solos, duos and trios. Newsreels featured the organ in separate screenings as a musical instrument with Martinelli singing Easter music and also as a scientific wonder.

Hope was initially engaged on a one time basis but Penny and Redmond were so pleased with her work that they engaged her on annual contract until Pearl Harbor eliminated consumer production. In recalling her initial introduction to Hammond, Hope once wrote," If they had only known, at the fee they named, we would have been willing to carry each Hammond organ into the customer's house as well."

Hope actually did more than help deliver the 1.400 organs which were shipped in the first year of production. While stodgy, company institutional advertising aimed exclusively at the church and institutional market explained the wonder of Bach on a Hammond, without neglecting the former razzle-dazzle. Hope promoted skating rink and race track installations to serve as pegs for sports-page headlines about "Avoir-dupois wins by two measure of Brahms" and "Skating to the Skater's Waltz."

Roosevelt gets a Hammond

When the Novachord was introduced in 1939, Hope arranged presenting the first one as a birthday present to Franklin Delano Roosevelt on Jan. 30, 1940. Eleanor Roosevelt, engulfed by reporters and newsreel men, personally accepted the Novachord at Hammond's own New York studio on 57th Street, then managed by Earl Campbell, now owner of Campbell Music Co. Washington D. C. and a past president of NAMM.

Hope also arranged a special Columbia record of "Happy Birthday," sung by Jan Peerce and Bidu Sayao accompanied by the Novachord. The first disk was presented to Eleanor Roosevelt during a Town Hall engagement and achieved wide and effective lineage.

Failure on bended knees

After the Industrial Arts Exposition in late April 1935, Penny barnstormed New England and the middle-west with the Organ and the Ford truck, a far-cry from today's Volkswagen, prospecting for dealers. Hanert and Penny after being rebuffed in Providence, R. I. personally manhandled the organ into M. Steinert & Sons auditorium and won the enthusiastic approval of Robert Steinert and Jerome Murphy, now owner of the firm and a Past president of NAMM.

Penny recalls one unsuccessful presentation made on bended knees. Venerable old Kramer of Allentown was so bowed by arthritis in his chair, that Penny had to get on his knees to look him in the face. Kramer, like many other merchants during those first months saw no commercial or musical future for "the gadget." "We are in the music business," he said. But the majority of merchants went wild over the organ and Johnny Jenkins of Kansas City and Perry Chrisler of Aeolian Co. St. Louis gave him a hero's welcome. Many confided at that time that the organ was the product that saved them during those bleak selling years.

An unknown Ethel Smith

Ethel Smith's unrecorded first association with the Hammond Organ occurred in 1939 when she walked into Philpitt's Music store in Miami to try the organ while Penny was there during one of his cross country tours. Unknown then, Penny recalls loaning Collins Driggs, then a Hammond staff organist, five dollars to take her out to dinner. A few years later Miss Smith was a celebrity in her own right after becoming firmly ensconced on George Washington Hill's American Tobacco radio shows. Since then, Ethel Smith's voluminous publications for the Hammond Organ have been a major force in Hammond exposure and sales.